Sexual Violence in the Humanitarian Sector

Despite the extensive internal ethics guides and external oversight, the inner workings of humanitarian organizations have increasingly become linked to harmful dynamics, including sexual violence targeting both other humanitarian workers as well as members of the population these humanitarians intend to assist. In an article recently published in International Studies Quarterly, Sarah E. Parkinson (Johns Hopkins University), Sofia J. Smith (University of Chicago), and I investigate the conditions that facilitate sexual violence among humanitarian aid workers.

In the article, we argue that three features that are integral to the setup of international humanitarian communities enable sexual violence. First, we argue that the dynamics of humanitarian work make it operate like a “total institution”, which means that people working within it are physically and socially separated from the wider society, and that the boundaries that usually separate different spheres of life (such as your work and home life) become blurred or disappear altogether.

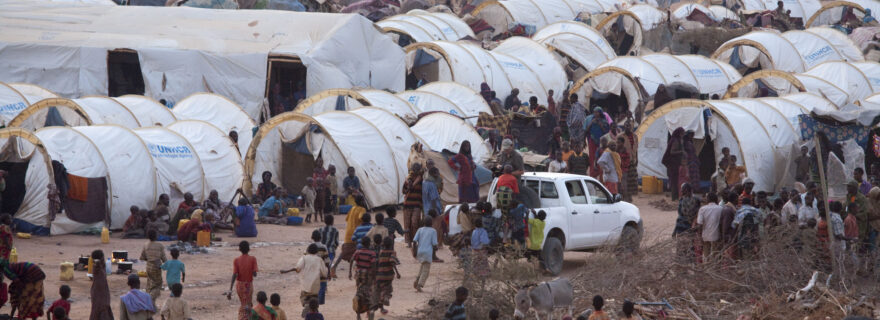

We then identify two more factors that are present in these communities that facilitate sexual violence. The first is the informal socialization dynamics. We find that how different life is in international humanitarian communities compared to other settings is leveraged to normalize unequal sexual power dynamics, make the boundaries of consent less clear, and enable forms of sexual violence. The second factor is the physical surroundings in which humanitarians operate. There is a lack of privacy between professional and personal boundaries. For instance, humanitarian aid workers in conflict zones often live in compounds where they might share bathrooms with their supervisors, and have very little private space. Or employers might control when and where their employees are allowed to receive guests, and whether they are allowed to spend the night. Humanitarian aid workers also often lack flexibility in their transportation options, making it difficult for them to leave a social event where they feel unsafe before the time they had agreed on with the company’s driver. Such social-ecological issues can make it more difficult for humanitarians to leave situations where they feel at risk of sexual violence.

In the article, we center how international humanitarian aid workers experience their everyday lives. We conducted in-depth interviews with humanitarian aid workers in Iraq and Uganda, and observed the dynamics of the international humanitarian communities in leisure spaces such as cafes, bars, and restaurants. We also analyzed texts such as blogs and 16 memoirs written by (former) humanitarian aid workers, which were recommended reading for new employees deploying to the field. We started the research in 2018, shortly after stories of sexual exploitation by international aid workers of members of local populations in crisis contexts such as Haiti featured in headlines around the world. We started studying the ethical challenges humanitarians faced when working in conflict-affected settings; the research was not initially focused on the dynamics around sexual violence. But in interviews the dynamics around sexual violence came up repeatedly without the research team asking about it. During participant observation these dynamics were further reinforced. The members of the research team existed in these humanitarian spaces, personally witnessing and even experiencing dynamics around sexual violence on numerous occasions.

In the article, we therefore aim to help understand why sexual violence is so prevalent within humanitarian communities, and offer several ideas on how they could be mitigated. We argue that solutions should not be aimed at “a few bad apples” but at structural issues within organizations and communities that facilitate sexual violence. For instance, training programs could address the informal socialization processes surrounding the dynamics of consent, as well as relationships between supervisors and employees. Transportation options could be improved, along with more options for privacy of humanitarian workers. Altogether, our research calls for a better understanding of the histories, designs, and cultures of relationships within humanitarian organizations, to come up with resources that could change the conditions that facilitate sexual violence.